It can now be revealed: in 1993 I returned to Yunnan in order to realize my childhood dream of becoming a tea baron. Yes, it all started in 1975 when I encountered the magnificent book by Robert Fortune, A Journey to the Tea Countries of China; Sung-lo and the Bohea Hills (1852), in which the intrepid Fortune manages to steal into the interior of China and abscond with the tea plants that subsequently helped to establish the British tea industry in colonial India. Disguised in wooden clogs, straw hat, and a wig with a long black queue hanging down his back, Fortune managed to punt along the waterways in the lowliest of riverboats. He dined on what he described as a miserable gruel, called congee, and reconnoitered the tea plantations and temple gardens along his route. Once, caught red-handed in a private garden while trying to steal a flower specimen, he was — instead of being turned over to the local yamen — given a nice cup of tea and a neatly potted living sample to take with him. Having yet to discover the reckless undertakings of Kingdon Ward and Joseph Rock, I was fascinated by the idea of botanist-explorer.

This of course led me to read various volumes on tea barons, tea manufacturing techniques, and to distinguish a broken orange pekoe from a souchong. Many a pot of oolong was brewed for me that year by the sympathetic owner of the Golden Dragon Chinese restaurant that once was located next to the Pyramid Adult theatre on Route 66. Later on, when I founded the tea club at Albuquerque High School in 1977 (with Tim Crews, Erik Stout, and Lars Tomasen), I thought becoming a tea baron was a fait accompli!

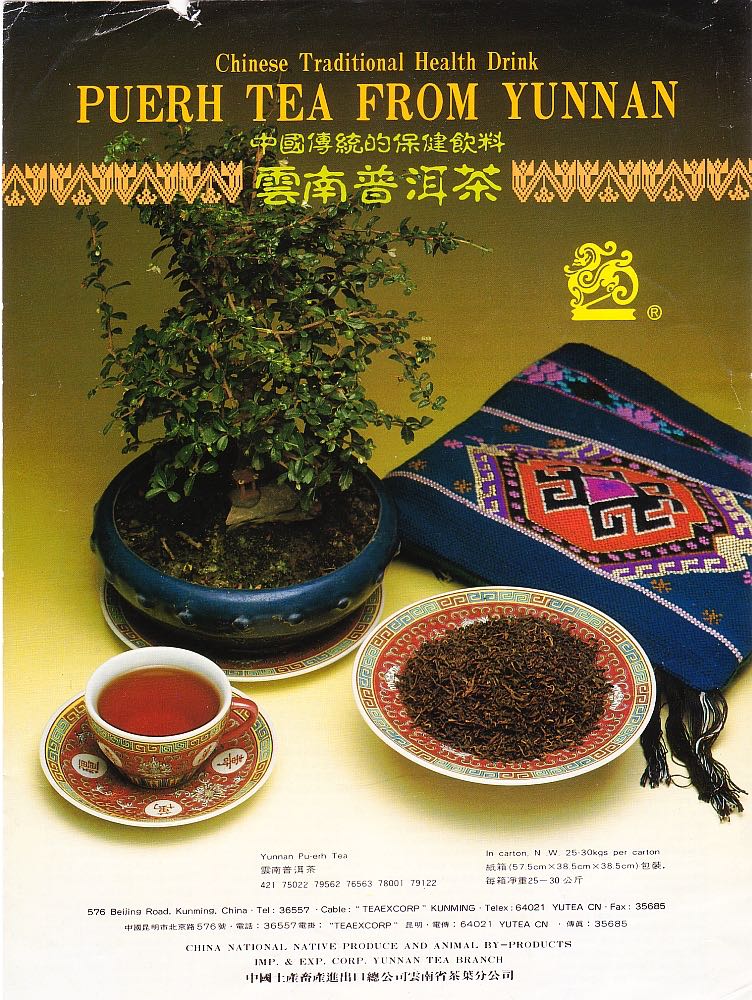

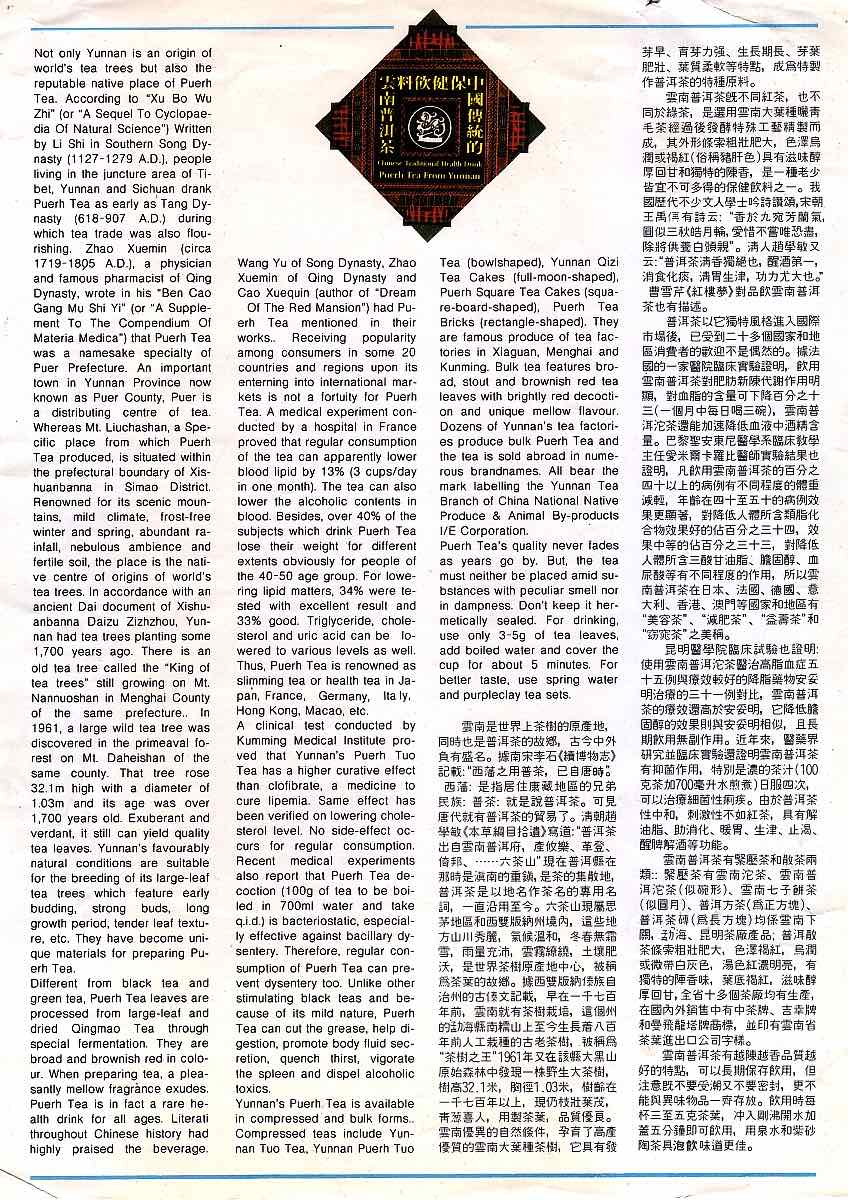

Little did I know, that tea is produced in quantities on the order of 3 million tonnes per year, and at the time of my venture to the China National Native Produce and Animal By-products Import and Export Corporation Yunnan Tea Branch that there was a total glut of tea on the market and thousands of unsold tonnes laying about at every market in sight. Nonetheless, I was introduced to the delights of various pu-erh teas, which have since then become my personal favorite… not the dessicated bricks of tuo-cha that look like donkey shit laced with straw, but rather the delightful, freshly dried pu-erh, which tastes of the very soil of Yunnan, a rich, hearty, unforgettable flavor as thick as coffee and tangy with minerals, pineapple sweat, and snake venom. The manager of the Yunnan Tea Branch gave me a wonderful descriptive flyer, reproduced here, for your edification:

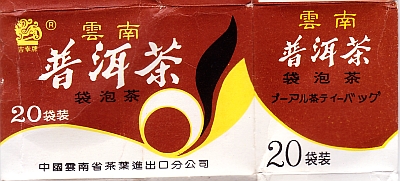

He also kindly revealed the secret of finding the best quality Yunnan pu-erh, to look for the lucky symbol on the tea package!

With this knowledge, I was able to sip the most incredible pu-erh every day for more than 15 years, at the cost of only 50 cents per box of 20 teabags! Alas, all good things come to an end, and in the last year the Lucky brand has vanished from the shelves of every Chinese grocery store that I have seen. From Boston to Portland, from Chicago to San Francisco, Lucky brand is no more! All I can do is to reproduce for you scans of the last package I had, sadly beat up, and only a fond memory of the fine leaves it carried…

Well, it’s not a total loss… even though the other brands of pu-erh typically found in Chinese groceries are awful, old leaves from yesteryear, still it is fairly easy to buy decent pu-erh from TenRen Tea Shops. Of course, now you have to pay $3 for 16 tea bags (or $50 an ounce for the good leaves), but if you are a pu-erh addict it’s well worth it.

On a similar note, I wanted to share a fond memory of one other tea that recently came my way, the Sikkim Temi Tea. I was given a box of these wondrous leaves by my brother Sangpo’s father, Phuntsok Dorje, who travelled to his hometown of Gontok and brought back a a 1/4 kilo. Sikkim tea is a delightful, crisp brew, like Assam tea with a clear freshness of the high Himalayas. Of course, having gone straight through this for my morning cuppa, it turns out to be nearly impossible to find outside of Sikkim itself, alas! But another fine remembrance of teas past…

Perhaps it goes without saying, but I should also mention that I discovered the delights of congee, more popularly known as zhou or xi fan, when I first visited Hong Kong in 1990. How can such a delicious and digestible dish — such as fish slices in congee — be considered even remotely related to the starchy and fetid abomination called gruel which Dickens served up to his starving orphans? Horrors! But don’t take my word for it, rush down to your nearest authentic Cantonese diner and ask for a bowl of yu pian zhou today…