The amazing thing about Ted White is his fantastic memory.

In a multi-hour interview, sponsored by the heroic team at Fanac, the editor, author, music-critic, and guru of science fiction fandom was introduced by Joe Siclari and Edie Stern, and was interviewed by John D. Berry.

White would occasionally apologize for missing a name or a detail, but that was like a toothpick floating in the deluge. The people, places, and events in his tale covered the last half a century, providing a window on the history of science fiction fandom that is both unique and fascinating.

Ted’s account of how he was first bitten by the radioactive bug of fandom: I had been reading science fiction in book form since 4th grade, stuff like John Cross Angry Planet. Although I had picked up copies of sf magazines on newstands and leafed through them, at that age I mostly read comics, and I thought the mags were over my head.

But in 1951, when I was in 8th grade, a friend gave me a few copies of mags from the previous year, and I read them cover to cover. I realized, I’ve seen this mag on the stands, they must have new issues! So I got on my bicycle and got the new issue, shocked to find out that the price went up from 25 to 35 cents.

I thought pulps were kind of low class and trashy. But through the pulps, I discovered fandom. Startling and Thrilling Wonder Stories both had fanzine review columnns, and they both had letter columns that were like miniature fanzines. The people were talking to each other, responding to one another’s letters from previous issues. (1)

These fans had their own argot: fanzine, prozine, and I thought I could tap into this social activity. I was the quintessential neofan.

One of the non-pulps that I enjoyed was Ray Palmer’s Other Worlds. It wasn’t distributed in Falls Church where I lived. I had to ride miles out of my way to find it. In Other Worlds there was chatty material in the letter column, and in the classified ads there was a free section for fans. I noticed that Warren Freiberg (in a suburb of Chicago) was advertising a copy of Superman #1. I was a serious collector already, delving into everyone’s basement to look for comics. I wrote to Frieberg and said that I was interested in the comic. We started corresponding and I found out he had a fanzine, Brevazine, which was the first fanzine I ever saw.

I was impressed and showed it to all my friends. I also started to write for Brevazine, and I had my first feud in that magazine with Terry Carr.

I was talking about Strange Adventures and Mystery in Space. Terry wrote this rebuttal saying you missed all the good stuff in E.C. comics. He was right, but I didn’t know it, because I had never seen them.

That’s how I got into fandom, through Warren Frieberg and his fanzine Brevazine. (2)

John Berry: how did you start to publish your own fanzines?

I put out my 1st in 1953. I did quasi-fan stories by writing to small comic fanzines, which are now extremely rare.

I was much taken by Brevazine which was done on a postcard with a mimeograph.

Our town had set up it’s new high school. We were designing publications and picking team mascots. I had done a cartoon, using a stencil for the school paper. I had no idea how to cut a stencil, but neither did they. I just traced with available light, and I wanted to learn how to do mimeo process and do it right.

I bought a postcard mimeo machine from Sears Roebuck, about $10 or $15, with cans of blue and red ink. I just started to stencil to learn how.

That fall was Stevenson vs Eisenhauer, at school we did mock elections, and I published a political postcard zine for that.

I was getting zines in the mail, Joel Nydahl’s Vega. I got involved very quickly. there was a column by Marion Zimmer Bradley, what every neofan should know. what to pub in your first ish. This was going to be ambitious. This was not something for me to approach casually. Which meant that I put it off.

In the summer 1953 I had the local chore of mowing lawns. The combined lawns of my parents and grandparents. It was a huge area. I convinced my parents to get a power mower, but they got an electric mower with a cable unspooling everywhere.

As I went around in figure eights, moving the cables, it took me all day to finish. But i had lots of time to think about fanzines and prozines that I wanted to do. All of this thinking came to naught. Finally, in August of 1953 it was a hot summer day, with no a.c. and the windows wide open.

I said: to hell with it! just do it! pub my ish!

But what material to use? I’d written some stories, and I’d done a bunch of drawings. Not much but a start.

By that time I had dealings with Dick Witter who ran F and SF Books on Staten Island. (3) At one point I bought a box of fanzines from him, all of them from the 40s. N3F (National Fantasy Fan) publications, Speer’s early fanzine, and there were stories by people I never heard of.

I blithely reprinted a bunch of that stuff. Never asked for permission. I was too naive and didn’t know how to get in touch with the authors.

I put the first issue of Zip out. It was a 4x6 zine. I used an elite typewriter on stencil and published 35 or 40 copies. (4)

I sent copies to Vega, but I was afraid to send them to Red Boggs, he intimidated me. I was afraid he would shit on my fanzine. Which in fact he did do, later, around the 3rd or 4th issue. He said: I won’t be turning the skyhook for these. (5)

John Berry: How did you start thinking about the design of fanzines?

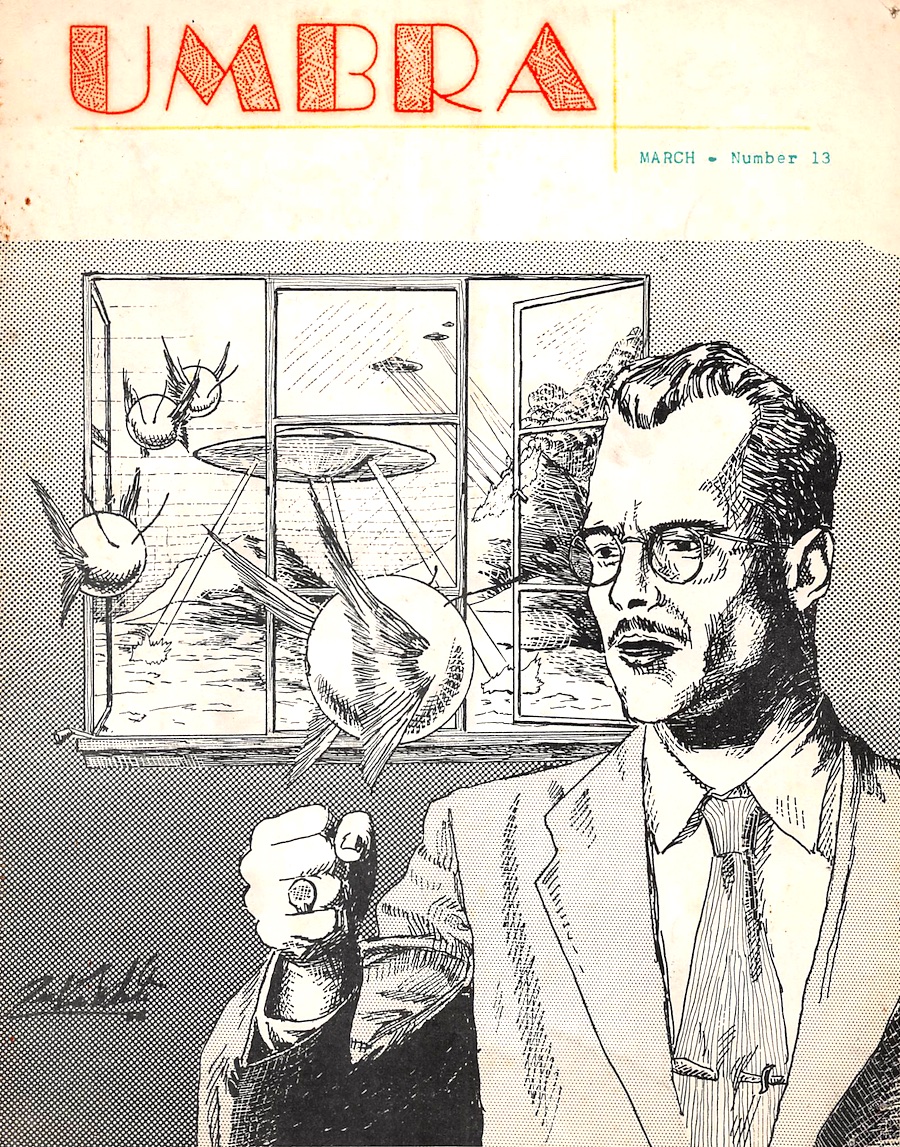

At 13 I regarded myself as an artist. I trained myself, had teachers. I learned pastels, and watercolors, and oils. Over the years I’ve done a lot of artwork, for example covers for Umbra, which was color photo-offset. You could buy very decent artwork at the dealer rooms at cons. I studied all that, how they did it.

There was a DC art supply place, with scratchboard, pens, solvents, zipatone (overlay sheets). I bought a bunch of all that stuff, brought it home and worked with it. I taught myself, as it turned out that my high school teacher knew nothing about the commercial art techniques. He was one of the people who called me mars boy, with contempt for science fiction and the people who read it.

I was really into design, the bauhaus, which I discovered at 14 or 15. I discovered experimental music. When I was doing cult zines, I would use bauhaus techniques, bars of shading above type, for instance.

I was going to the museums in DC, studying the classics, and I found Mondrian. He was an incredible genius! Without Mondrian we would never have modern graphic design.

John Berry: How did you move to new york?

Ted: I knew it was inevitable on some level. As I was growing up in fandom, NYC was the epicenter of everything SFnal. It’s where all the publishers were, especially after Ziff-Davis left Chicago. And it wasn’t just SF. It’s also where all the major record companies had their headquarters.

When I was doing Gambit (before Void) in 1958 I started reviewing jazz records. I wanted to write those reviews professionally.

Everything came together in New York… Once when I stayed at the Nunnery on Cooper Square, and discovered Charlie Mingus was playing literally in a bar across the street. (6)

When I moved to NYC basically it was to begin a career in jazz criticism and journalism. The kick that sent me to new york was that I married Sylvia in Nov 1958, and we moved into an apartment on North Charles Street in Baltimore. It was in a series of row houses. We had the top floor. The other people who lived in that building were “elderly” and they took offense at the sounds of us going up and down the stairs after about 7pm.

They’re tromping like a herd of beasts up and down the stairs, keeping us awake all night.

The landlord evicted us, but he gave us time to find a place. We found another option in Baltimore, but at the same time, why move to the familiar? I know I’m going to end up in NYC, I guess it should be now.

So in July and August, Sylvia and I went the NYC many times and went apartment hunting. We stayed at the “nunnery” famed in fannish song and story, the site of a con between x-mas and new year 1958.

Dan Steffan said sure there’s spare beds to sleep in here (at the nunnery). But we didn’t have much luck in apt hunting. One place we saw was on the South side of Houston street. The building was tall enough to have elevators and the apt was on the ground floor, with the only window at the bottom of the air shaft. There was furniture in this place and it was only about 40 dollars a month.

But it was so dark and so dismal. I ildy opened the dresser and in the drawer I found WWII ration books. That was a sign of how long ago the last occupants were there.

The place we ended up with was Christopher Street, for $68 month, it was a 4th floor walk up.

The first thing I did was make the rounds of music magazines. DownBeat and Metronome. When I first got DownBeat it was a folded tabloid. By the late 50s, it was a regular magazine.

Metronome was older. It got started in the late 19th cnetury with marching bands, then evolved into a jazz magazine, and it had interesting opinions. The editor was Bill Coss, he wrote subjectively in an interesting way.

I put together my portfolio of record reviews, books about jazz and reviews of the first club dates I’d gone to since I arrived in NYC.

The first thing I found out was that DownBeat wasn’t published in NYC. it was a desk in an office. there was a guy named George Heffer who explained things, took copies of my portfolio and said he’d send them to chicago.

The editor, who had an irrational hatred of rock music also hated me. He rejected my material.

Then I went over to Bill Coss, and we had a great conversation that lasted over an hour. He said he would look at my portfolio. But my timing was bad, because shortly after my meeting with Bill, they went on six month hiatus. So I had a long wait. But when they resumed the magazine, they had a new art director, and it was a marvelous improvement. It made a big splash. And I made a big splash because they had included my writing about Ornette Coleman.

I tried to explain what I thought the music was about. Coleman said it was the best article on his music, and I was able to establish myself.

Still, it was a rough period. Sylvia and I got by on very little money. Some weeks we survived on a loaf of bread and bar of stolen cream cheese. I pawned a lot of stuff. Sylvia hocked her piccolo. I hocked my slide rules.

I had little successes. I sold a piece to Playboy and opened my first checking account to deposit their check. (7)

I could get 10 to 25 bucks a throw for a piece, but we struggled a lot to get by. Metronome would never use more than 2/3 of the reviews I was sending them.

John Berry: How did you get into writing and editing science fiction?

I always wanted to. I’d been writing short stories since I started in fandom. Marion Zimmer Bradley said my stories had good ideas and could be developed, which was encouraging.

But I was still going full blast with Metronome. I met this guy doing a radio show, with jazz programming from 6pm to midnight. I called him up and asked to write for him. It so happened that my Coleman interview had come out, so he invited me to do a bunch of things.

We were sitting in the Five Spot Café one night, and we agreed that there was barely enough money in the entire jazz writing field to support three writers, but there were already more than a dozen of us! And that was including big names like Nat Hanhoff, who took the lion’s share. So I realized there wasn’t enough money to support us, and I had to find something else. (8)

There was no future in jazz writing. Therefore, writing science fiction was the logical and inevitable next step.

One day I was walking down 7th Avenue thinking about A E Van Vogt’s better stuff. What were the components that made it memorable? When I got back to the apartment, I thought: HUH! let’s try something here. I was using a portable typewriter on the kitchen table.

So I banged out several short chapters, adhering to the “new idea every 800 words” the Van Vogtian paradigm. And I had a paranoid plot: they really ARE out to get you!

I wrote this opening, in the summer of 1961, and then it just sat there. I had gotten enough on paper to know what the story was and could pick it up later.

The following spring, I went through a lot of personal turmoil surrounding the end of my first marriage. I found myself in New Haven, Connecticut and I had a stretch of time with nothing to do. Out of boredom I cranked a sheet of paper into a typewriter and started to write. I finished about 3/4 of a short story, unsure of the ending.

Then I went back to Brooklyn where I was by myself. On the drive back I thought about how to finish the story, which I called Phoenix. When I sent it to several mags, they all rejected it.

Then I sent it to MZB and said, remeber you said you wanted to collaborate with me? Do you want to try to do something with this? She revised it and made improvements, calling it New Phoenix. When she sent it to Scott Meredith, he sold it to Amazing Stories. (9)

Meanwhile, I dug out the opening of the Van Vogtian novel. I thought of Bob Tucker, who was a big influence on me, in the way he could mine his own material, cannibalizing his own stories and get a novel out of it. I also thought I could get a short story of that novel. I did that, and asked Terry Carr to look at it and run it through his typewriter. We had sometimes written pieces of each other’s editorials and we had a really good relationship. After Carr edited the story, Fred Pohl bought it for If.

I got word of the sale of BOTH of these stories on the same day, in August of 1962. To this day, I still have no idea which was my first sale because the issues of If and Amazing came out the same day on my newstand in January of 1963. So I guess they are both my first story.

John Berry: So you were back in Brooklyn where you hosted the Fanoclasts, and you were organizing a bid for Worldcon 1967, NYCON III. You were co-chair.

I had been friends with Ray Fisher and his wife Joyce. Ray was in sixth fandom days, but they’d been out of touch with Fandom for ten years. They didn’t know about putting on a con, about parties, or anything. We got to know them and others in St. Louis fandom. We boosted the couches for them, and they were helpful boosting us. They worked behind the bar in our room parties and things like that. So on one level it was a connection between NY and St Louis fandom that gave us some momentum.

But the main reason was that a bunch of us went to Philcon and we were coming back together in the same car. I know Rich Brown, Mike McInerney were in that crowd, and even John Boardman. We started talking about gossip from the con. Jack Chalker was going to bid for Baltimore for 1967 Worldcon. None of us had a high opinion of Jack Chalker. He wasn’t an author yet, and he was not well liked as a fan. We were repulsed by that idea, and thought that even we could bid for a worldcon.

That was the origin of it. We started talking about it and got more serious. My notions were based on all the histories of New York City fandom. We were famous for our fractured fandom, dating way back to the 40s or 30s. Fans warred with each other continuously. Will Sykora’s Queens club warred with David Kyle’s futurians

There was the early case of a New York bid being announced and then another competeing New York bid was announced from the floor, a seat of the pants bid. The New York bids cancelled each other out. So New York was famous for this fractious, warring situation. Look at NY CON II, the thing ended in lawsuits where half the committee was suing the other half. (10)

Consequently nobody wanted to see another con in NYC. Some people said you need to get a committee together of all the parties working together.

But I said no, that’s how you get friction, and end up with lawsuits.

I thought: let’s use the Fanoclast rule where everybody has to like you. Any member could veto or blackball a newly nominated member. Owing to this, we had people who worked pretty well together. It was a functioning anarchy. There were no business meetings. None of that crap. We just molded our relationships into that bid. We had Felicity doing comics for us. we had Harlan Ellison as a nominator. We had a slick campaign that we were proud of and we won the bid. (11)

![]()

For programming I thought we should do some things I want to see at cons and eliminate some things that I didn’t like.

We didn’t want to have a bunch of panels with five or more people where only one dominates. I thought we ought to just eliminate the panelists and make it a dialog between two people.

We had Chip delany talking to Roger Zelazny, Judith Merrill talking to Tom Disch, Norman Spinrad talking to Fred Pohl, and John Brunner talking to Fritz Lieber. We didn’t need more people on the stage, it just had to be an interesting conversation. (12)

Lee Hoffman

Lee Hoffman I first met in person at Worldcon in 1955. (She was the publisher of Quandry one of the great fanzines.) But we knew of each other from FAPA. She was nice towards me as a neofan. I sent artwork to her fanzines, including a cover for Gardyloo.

She taped a band singing folk blues and sent it to me. I was a guest of her and her husband Larry Shaw, sleeping on their floor in the living room.

Lee Hoffman wasn’t in any of the four or five fan groups in NYC. When Sylvia and I got in touch with her, she thought we should get together for go-kart racing. She must have been doing that regularly.

It was in mid-town manhattan, down 7th avenue where there as a big parking lot taped off for the go-kart track. I met her there and got to sit on the cart and drive the cart around the course several times. Damn you’re close to the ground in those things! (13)

Some years later, Lee became an attending member of Fanoclasts, when we were meeting in my apartment in Brooklyn. She brought over the Risen brothers, Joe and Don, who lived in unique loft off 16th Street, in a three story building. They had top floor of commercial building, where you would shout up to them and they lowered a key on a string that you used to unlock the door.

They had us over for parties many times, once they had a roast suckling pig in 1964. Joe apologized for having to put a second apple in its mouth. Don Reisen helped me with my car when I had to go to the Bronx to fix it.

Lee was shy, she could relate to people, but she didn’t seem to enjoy large groups of people. I found out she was an artist. She gave me a painting and later gave me a soapstone sculpture she’d made. I had just been published and I was bubbling with enthusiasm. Lee picked up on that energy and she went to write fiction herself. She was writing a western story and showed me the first chapter. She asked me should I continue? I said yes, this is great stuff! Then she sold it to Ace books, and wrote several in a series that I read in manuscript.

Lee stayed in fandom publishing the fanzine Science Fiction Five-Yearly that continued up to a month before her death.

The next issue of SFFY was due out that month. I was overdue in sending in my piece on Harlan Ellison, which was a quasi true story, based on a series of real events. In my story, Case #770 Harlan was ousted from his editing job by Algis Budrys and went to the West coast. The piece was about a detective being hired to track down Harlan, a send up of a Raymond Chandler private eye story, drawing upon the fannish world, including Lee’s actual apartment, with the cave painting on the wall.

Sadly, Lee never had a chance to read it. Jerry Sullivan and I agreed that I would record a spoken word reading of the piece for Lee to hear but we hadn’t quite done it yet before she died. And I was incredibly disappointed that she didn’t read it because she would have appreciated it.

Gee, among the main characters: Harlan Ellison, Aldis Budrys, Earl Kemp, Lee Hoffman and myself, I’m the only living person related to that story.

John Berry: What about Fan Writers of America?

It was the 1974 worldcon in Los Angeles. The con hotel was across the street from Disneyland. It was a wierd hotel and the first room I was given was a big wedge shape with windows on two sides with inadequate a.c. So I moved to a more interior room, but the ac in that hotel was primitive. There was some unit in the ceiling over the bathroom that fed air into the main room, it was entirely recirculated, and the windows did not open.

I had room parties at night and there was a lot of smoking of tobacco and other substances. Whenever I left the room for a while and came back in, it was a fetid wall of stale air. But I kept having room parties, and one of them was THE room party. There must have been 20 people in there; every surface was occupied; and there were lots of good ideas being kicked around.

I realized it was 9 or 10 at night and someone was missing. It was Lucy Hunsinger. She did come over and people started kicking around the idea, as in a fanciful way, about the Science Fiction Writers of America. We were mocking it and ridiculing it. We thought of founding the Fan Writers of America.

I think it was certainly a group effort, and there are some other accounts of it published in fanzines, by people who all contributed. But I picked up the ball and ran with it.

The Fan Writers of America was a farce, of course. We said that in the interest of American imperialism that America by extension must include the entire world; therefore all fan writers in the world were elibile to join. As for membership: whoever regarded themselves as a fan writer was automatically a member.

In order to destroy the opportunity of business decisions, power plays, even if there were officers, we made up a rule that nobody could be a present officer. We would only have past officers. Then we would pick our president from among the people who attended the previous year. That way we recognized a past president, for their previous efforts, but never allowed for a president to actually serve in any capacity in the present time.

Based on this idea we picked a few presidents, but it didn’t gel until the Seattle worldcon, and then it became an annual event at the Corflu, where we would always vote on the past president. People would come up to me and ask who I would pick, and I’d say I hadn’t decided. So I asked them who they were thinking about, and they would tell me. I’d say: nominate them! That’s how so many people ending up being nominated who I would never have thought of.

It’s a fun tradition that has absolutely no meaning. You can put past president after your name, if you were one. The whole concept is to honor people who’ve done some good fan writing.

That effort never gets sufficient recognition, though it deserves more.

Whither fandom?

“My theory of fandom is that is an an anarchistic meritocracy. Nobody runs it; never has; never will. It’s totally voluntary in nature. You rise in fandom on benefit of your talents and abilities, and it doesn’t matter if you’re male, female, young, old, or indeterminate gender either. It doesn’t matter.

You can present any persona you want, but if you’ve been around long enough your true persona will come out.”

– Ted White

References

(1) One noted case of letter column history is that Fred Pohl and Isaac Asimov both had letters appearing in Thrilling Wonder Stories of June 1939. A scan of the letters reveals Asimov’s boast: if I am wrong, I guarantee that I will build a spaceship, fly to Uranus, and eat it whole. See Jesse Willis, SFFAudio

(2) Ted White on Comics, Part II by Bill Schelly, in Alter Ego #148 (Sep 2017)

(3) Dick Witter’s F and SF Books was also the distributor of ALGOL 1963-1984, edited by Andy Porter.

(4) Zip lasted seven issues (1955-56), then the title was changed to Stellar and later Gambit.

(5) Redd Boggs published the influential fanzine [Skyhook-](https://fanac.org/fanzines/SkyHook/ in Los Angeles, 1948-1957.

(6) Memories of the Nunnery by Bill Danaho Habakkuk v3.3 1994 p.26

(7) Apparently this piece was an anecdote about Algis Budrys for the column “After Hours” and never saw print. Ted White said he did cash the check, though.

(8) Making A New Kind Of Scene: New York City’s Five Spot by David Johnson (2020-06-25)

The Bet by Ted White

(9) Scott Meredith agency became a hub for science fiction writers, many of whom got their start writing porn. Meredith created a scheme of sending the manuscripts from a post box under a false name, and using black boxes to differentiate from his typical gray mailers. An excellent account of the black box gang is in Nobody Can Write This Shit Forever by Earl Kemp, eI 13 (Apr 2004).

(10) White was himself one of the balcony insurgents, who created an incident by refusing to pay for an overpriced dinner and demanding to sit on the balcony to hear the GoH speech. This resulted in the immortal phrase, “Dave Kyle says you can’t sit here.“

(11) Photo of Ted White and Harlan Ellison making the Nycon 3 bid was taken at Tricon in Cleveland 1966. Photo by Jay Jay Klein. src

(12) Nycon 3 Program

(13) Lee Hoffman’s go-kart memoir.