There is something fascinating, unfathomable, and mystifying about the Caucasus Mountains, and the peoples there, scattered among the modern nations of Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and spilling across the borders into Russian Dagestan, Ossetia, Chechnya, as well as into Turkey and Iran.

Ancient mystical knowledge seems to flow from the hidden valleys, protected by layers of fierce local tribes and impenetrable customs. Residing in the open country and the high mountains where others feared to tread, the many peoples of the Caucusus region were reputed to be bandits and savage fighters, while at the same time famous for their courtesy and curiosity for all travelers from foreign lands.

Codes of honor bound people to their lineages and their lands, and grievances between tribes of different ethnicities and religions were handled by the atamans, the clan chiefs, according to age-old traditions.

What strange forces percolate up from the hills and across the treacherous mountain paths to bring so many seekers and tribes together?

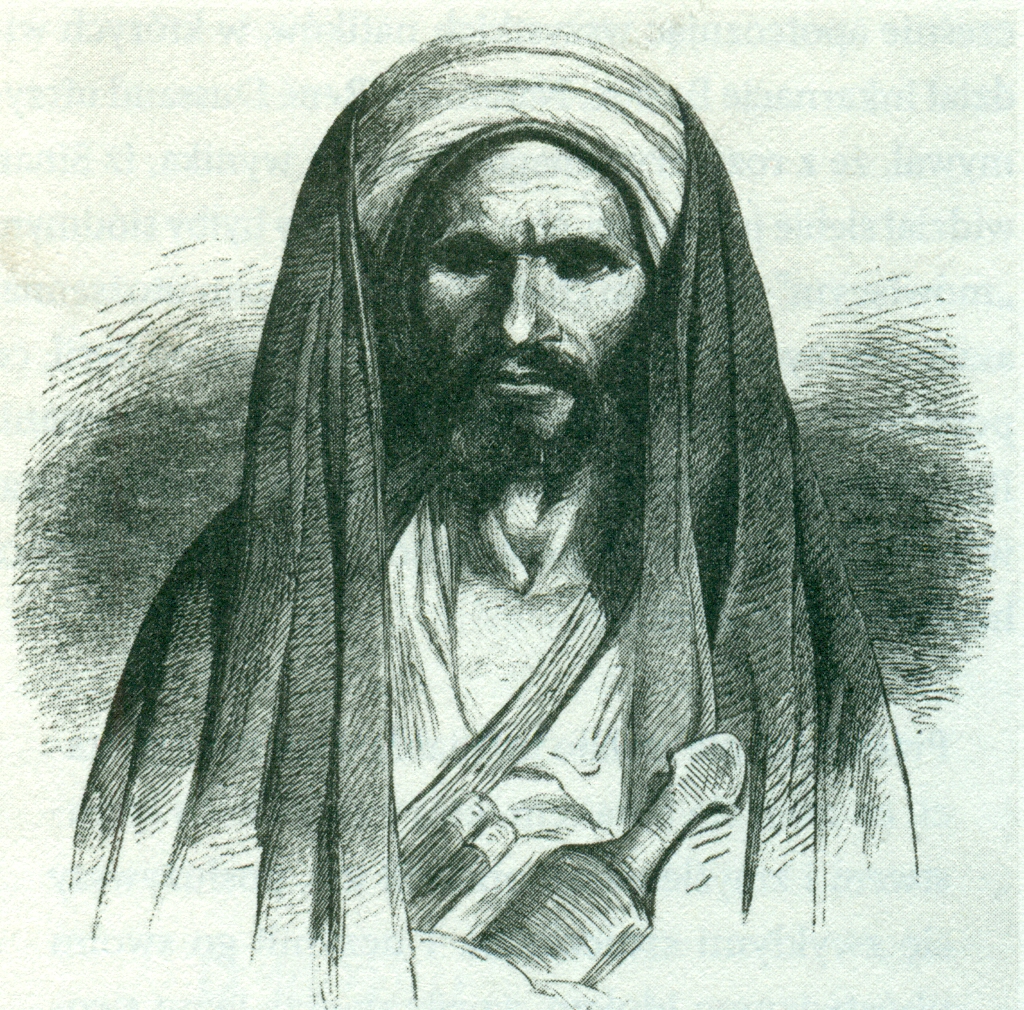

From the Southern flank of the Lower Caucusus, stretch the Alborz Mountains of Iran, the actual lair of Hasan-i Sabah and his fanatical followers, the hashshashin.

Hasan-i Sabah’s mountain fortress at Alamut was the headquarters of the Shi’a Nizari Ismai’lis during the 11th and 12th Centuries. ‘The fortress was thought impregnable to any military attack, and was fabled for its heavenly gardens, library, and laboratories where philosophers, scientists, and theologians could debate in intellectual freedom.’ Wikipedia

In 1256, Ruknu-d-Dīn Khurshāh surrendered the fortress to the invading Mongols, and its famous library holdings were destroyed. Was this the secret library and tradition of the Ancient Ones?

Why are the Caucusus like a vortex of intense mysticism and spirituality? Is it the unspoiled and rugged terrain, which only the strongest and most desperate of souls can survive?

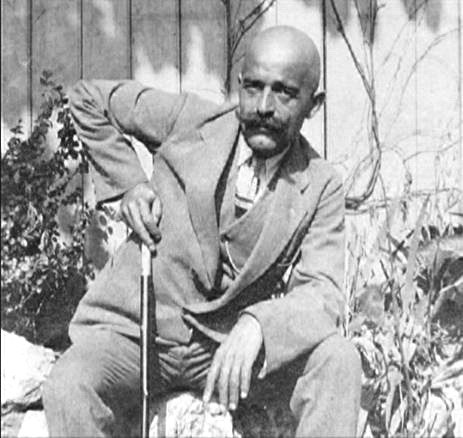

It is here that Gurdjieff was born, shortly after the Circassian - Russian War, in the Russian-controlled city Alexandropol of Eastern Armenia. Brought up in the Christian tradition, the young Gurdjieff considered becoming a priest, before his quest for mystical knowledge propeled him outside of the Church and onto a life quest for mystical truth.

The story of Gurdjieff’s youthful quest is told in his autobiographical book, Meetings with Remarkable Men, in which he spins fabulous tales about his encounters with members of a secret brotherhood who are all seekers of truth. Gurdjieff claims that his wanderings led him to travel to Central Asia, Egypt, Iran, India, and even Tibet. Gurdjieff claimed that he eventually found the secret monastery where the ancient teachings of the Essenes were preserved by the Sarmoung Brotherhood.

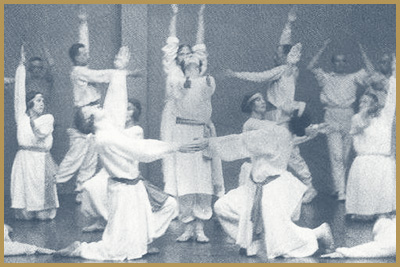

Among the sacred rites of the Sarmoung Brothers and Sisters, were complicated forms of ritual dance, and so it is not so surprising to find that in the early years after his mystical quest, Gurdjieff became the organizer of ballet and dance performances in Moscow, while at the same time gathering disciples into a mystical school. The complex, early teachings of the school, focused on the body, mind, and spirit being simultaneously advanced towards higher consciousness. The combination of all three factors became known as The Fourth Way.

The influence that Gurdjieff had on the movements of “alternative spirituality” in the early 20th Century cannot be overlooked. His origins in the Caucusus and his far-flung quest for mystical truth, provided grist for the mills of the Theosophists, and a host of other knowledge seekers.

The film adaption of Meetings with Remarkable Men), by British director, Peter Brook, is an inspiring production, that follows the young Gurdjieff from childhood through his mystical revelations and journeys. The evocative scenes (filmed in Afghanistan), capture some of the feeling of a lost world of traditional mountain tribes.

The music in the film is also quite good, weaving in and out of the scenes with sinuous presence, it helps to transport the viewer along the labyrinthine route of Gurdjieff’s singular quest.

Another nice thing about this film is the pacing, which is both sedate and yet enervating, driven by the passionate quest for secret knowledge that forces the protagonist to undertake all sorts of mad adventures and risks. Only rare moments of insight provide the sustenance for the hero to continue his journey, as in the scene with the Prince Lubovedsky in Egypt, who is another seeker of the high road.

Peter Brook is a brilliant director, by all rights, (his play Marat Sade is an unparalled classic; and his film version of King Lear is pretty damn good, too); but in this film he manages to imbue the story with the raw feeling of Gurdjieff’s path.

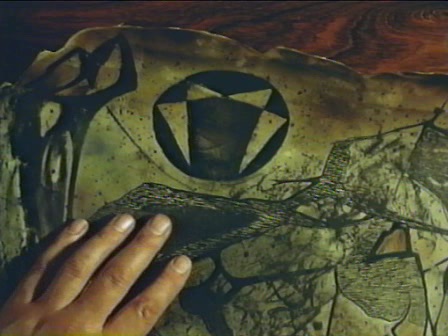

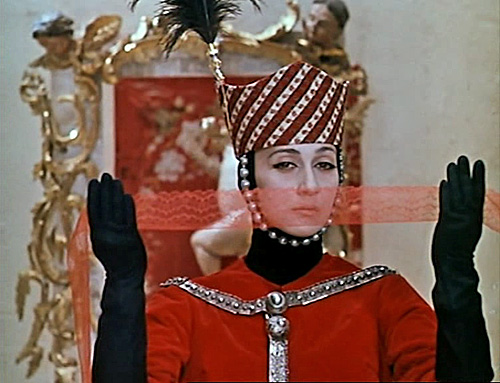

Yet another oddity of the spiritual quest in the Caucusus is seen in Sergey Panjarov’s The Color of Pomegranates, (1969), which portrays the inner life of an 18th Century Armenian Poet, Sayat Nova.

This bizarre and purely symbolic film is sometimes heralded as the “best film ever made.” For example, Martin Scorcese, who was instrumental in the film being restored and released on DVD in 2015, had this to say:

“Watching Sergei Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates is like opening a door and walking into another dimension, where time has stopped and beauty has been unleashed. On a very basic level, it’s a biography of the Armenian poet Sayat Nova, but before all else it’s a cinematic experience, and you come away remembering images, repeated expressive movements, costumes, objects, compositions, colours.”

There are certainly some astonishing visuals in this movie, which has been making the rounds of special showings in the last few years, and which I happened to see recently thanks to the Davis Center Film Series.

If you think of it as a long, slowly evolving image, in which symbolic representations of a poet’s suffering are rendered in heavy, ponderous posturings, then you will get the most out of it.

For others, including me, there were just too many scenes of heavy-handed religiosity, crowds of sheep, hands over faces, seashells on breasts, rivulets of red (like blood, but maybe pomogranates!); and it was just a bit too much.

If the music had been something like the eerie and sad duduk of Djivan Gasparyan, I might have had a really different experience. Maybe I will try to watch this Panjarov film again, silently.

I can’t help wonder if there isn’t something in the soil of the Caucusus that drives people to ponderous spiritual journeys. It’s like a magnet for the soul-searching madness.

Of course, maybe it helps to have Mount Ararat smack in the middle as well. Tim Powers had a bunch of fun with that setting in his dark magic and espionage novel, Declare.

There is something in that soil, or that water, or that brandy from the vines of the Caucusus.

As Gurdjieff himself said, in Tales of Beelzebub’s Grandson:

“And now, before setting to work on the second series of my writings, in

order to give it a form accessible to everyone, I intend to rest for a whole

month, to write absolutely nothing and, for a stimulus to my organism,

fatigued to the extreme limit, slow-ly to drink the still remaining fifteen

bottles of “super-most-super heavenly nectar” which at the present time is

known on Earth as “Old Calvados.”

This Old Calvados, by the way—twenty-seven bottles of it—I was

considered worthy to find by accident buried under a mixture of lime, sand,

and finely chopped straw, several years ago when I was digging a pit for

storing carrots for the winter in one of the cellars of my present chief dwelling

place.

The bottles of this divine liquid were buried in all probability by monks

who had lived in this place, far from worldly temptations, for the salvation of

their souls.

It now seems to me that it was not without some ulterior motive that they

buried these bottles there, and that, by virtue of what is called their “intuitive

perspicacity”—the data for which, one must assume, were formed in them

thanks to their pious lives—they foresaw that this divine liquid would fall into

hands worthy of understanding the meaning of such things, and that it would

stimulate the owner of these hands to sustain the meaning of the ideals on

which the corporation of these monks was founded and assist their better

transmission to the next generation.

During this rest of mine, fully deserved from any point of view, I wish to

drink this splendid liquid, which alone during recent years has given me the

possibility of tolerating, without suffering, beasts similar to myself around me,

and to listen to new anecdotes, and sometimes for lack of new ones, old

ones—provided, of course, that the storyteller is a good one.”