In a recent interview, Ted White talked about his early career as a jazz writer, when he was hanging around in the clubs of Greenwich Village, and how he first got published in Rogue Magazine. His comments sparked my curiosity about that magazine, which was a magnet for talented and eccentric writers and editors. How did a semi-sleazy magazine for men become a cross-roads for so many talented writers and editors? And why were so many of them writers of science fiction?

The best accounts that I could find to corroborate Ted White’s recollections were those of Earl Kemp and Frank Robinson, who were also employed by Rogue in the late 1950s. The picture that emerged from these sources is one of a fast and loose enterprise, that made a quick buck in the gray area between a changing, more permissive society and the political conservatism that tried to enforce its own definition of what was obscene. As the unlikely protagonist in this conflct, Rogue Magazine became a free-spirited canary in the coal mine, and survived multiple legal actions to halt its distribution.

Based in Chicago, Rogue was founded by William Hamling, as a competitor to Playboy Magazine. There are conflicting accounts about the origins of Rogue. Some eyewitnesses recount that Hugh Hefner and Hamling were working together on mockups for a prospective men’s magazine as early as 1952. Did Hefner propose to Hamling that they run the magazine together as partners? Whether or not there was an actual deal that went sour between them, Hefner published the first issue of Playboy in December, 1953. The magazine was a huge success. And almost simultaneously Hamling pursued the idea of setting up a competitor.

Hamling couldn’t hope to match the flamboyant launch of Playboy, with Marilyn Monroe on the cover, but he did have a talent for finding some great editors and writers. Why were so many of them involved with science fiction?

The answer to that question can be traced back to the mid 1930s, when Hamling attended the Lane Technical High School in Chicago. There were at least six sf fans attending that school, where Hamling edited the school newspaper. He was involved in the formation of Chicago’s earliest fan organizations, the Chicago Science Fiction Leauge, and the Chicago Science Fictioneers, and was peripherally involved with the second Worldcon that was held in Chicago in 1940. An acti-fan from the beginning, Hamling also published a fanzine called Stardust which was known for it’s high production values.

In 1947, Hamling got hired by Ray Palmer who had been editing Amazing Stories for Ziff-Davis. Within a few years, Hamling had been promoted to managing editor for both Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures. That explains why he knew so many of the top writers in science fiction at the time.

When Ziff-Davis closed it’s Chicago operations and moved to New York, Hamling embarked on his own independent publications. He took over the science ficton digest, Imagination, in 1951, and was able to lure contributors from the stable of writers that he’d been working with at Ziff-Davis. When Hamling launched Rogue Magazine in 1955, it was a 35¢ newsprint tabloid, and it remained a pulpy second-rate mag until May 1959, when the price was increased to 50¢ and Rogue Magazine became a slick.

Surely, Hamling’s background in the sf pulps explains why Rogue Magazine published so many sf writers, including Silverberg, Beaumont, Bloch, Budrys, Shaw, Bester, Mack Reynolds, Lieber, Ballard… a regular rogues’ gallery of sfnal talent!

From the start, Hamling and editor Frank Robinson, looked for hungry young writers and sought to give the magazine a literary tone, punching up at their cash-rich competitor, Playboy. Hamling also brought Harlan Ellison onto his staff as associate editor, a position which Ellison used to tout himself and the magazine all over the country. Ellison was promoting his new job at the magazine like nobody’s business, to such an extent that another acti-fan, Bob Tucker, complained that he spent an entire evening listening to Ellison chew his ear off about Rogue in July 1959.

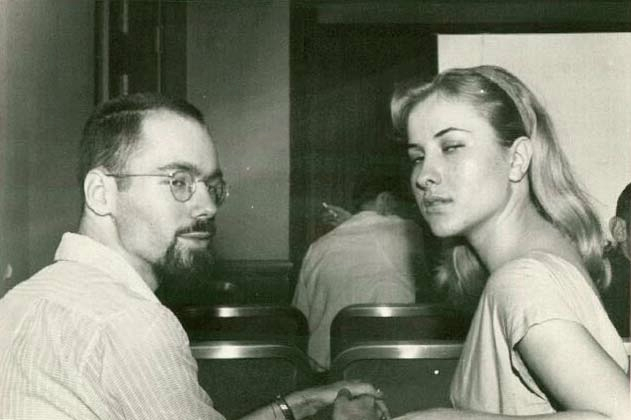

In New York City, Ted White found out that his old friend, Harlan Ellison, had joined the staff of Rogue in Chicago, and when they next had a chance to meet, (at the Worldcon in Detroit), Ellison actually paid him for a story title that White came up with on the spur of the moment. For a writer just getting started in his career, getting paid for anything was a big deal. So Ted White continued to send snippets and story ideas to Ellison.

But it wasn’t until the summer of 1960 that White sold his first story to Rogue. That happened when Harlan Ellison went to New York and stayed at Ted White’s apartment on Christopher Street. It was July, less than a year after White had moved to the city to try his hand at being a jazz critic. The plan was for Ted White and his wife, Sylvia, to drive up to Newport for the Jazz Festival, while Harlan Ellison would watch the apartment.

When he got to Newport, White was denied entry to the main festival where his press credentials, as a reporter for Metronome, weren’t accepted. He drove around Newport, where crowds of young people were arriving from all over the country. They didn’t look like the usual jazz nerds. The festival sold out and all the people who couldn’t get in started drinking and having a party in the streets

Although White couldn’t get into the main jazz festival, he found out about the anti festival being held nearby at the Cliff Walk Manor. The origin of the “rebel festival,” as it came to be known, was an ongoing legal dispute between Elaine Lorrilard, who co-founded the Newport Jazz Festival with her husband, and the festival manager, George Wein. As an act of defiance, Elaine Lorrilard organized her own counter-festival in 1960. She recruited Charles Mingus to line up the acts.

As he circled around town, Ted White saw Mingus riding in a big convertible with the top down. He followed the jazz musician, who was playing in the open car along with a few members of his band and calling out to the crowds on the sidewalk, “Come to my festival!”

In the same slow parade, White saw trouble-makers who were mooning the crowd from other cars, baring their asses and tossing beer cans in the street. Things were getting that rowdy by mid-afternoon.

When the anti-festival got started that evening, it was clear that Mingus had put together a terrific set of performances. At the smaller venue of Cliff Walk Manor there was outdoor seating for only a few hundred people. At first, nobody there was aware of the chaos erupting nearby.

White described the event in “Tale of Two Editors” :

“That evening, while listening to Ornette Coleman… my eyes began to sting, and I realized that we were being tear-gassed – the tear gas drifting from what turned out to be a riot at the main festival.”

When the rioting broke out, Ted White was sitting on the fringe of a cloud of tear gas that the police laid down in the center of Newport. The cops were trying to quell those crowds of boozed up, thrill-seeking kids who were going wild. Close to two hundred people got arrested, and one hudred sixty more ended up being treated for injuries in Newport Hospital.

For small town America in 1960, it was a shocking, wild scene. Ted and Sylvia got into their car and headed up to Boston around midnight. There were roadblocks set up all around Newport.

“The police were letting people out,” said White, “but they weren’t letting anybody in. It was like that.”

When they reached Boston, White called up Harlan Ellison back at Christopher Street, and told him what was going on at the jazz festival in Newport. Ellison thought that White’s account of the riot would make a perfect piece for Rogue Magazine, regardless of the fact that White wasn’t actually an eyewitness at the main festival where all the rioting took place.

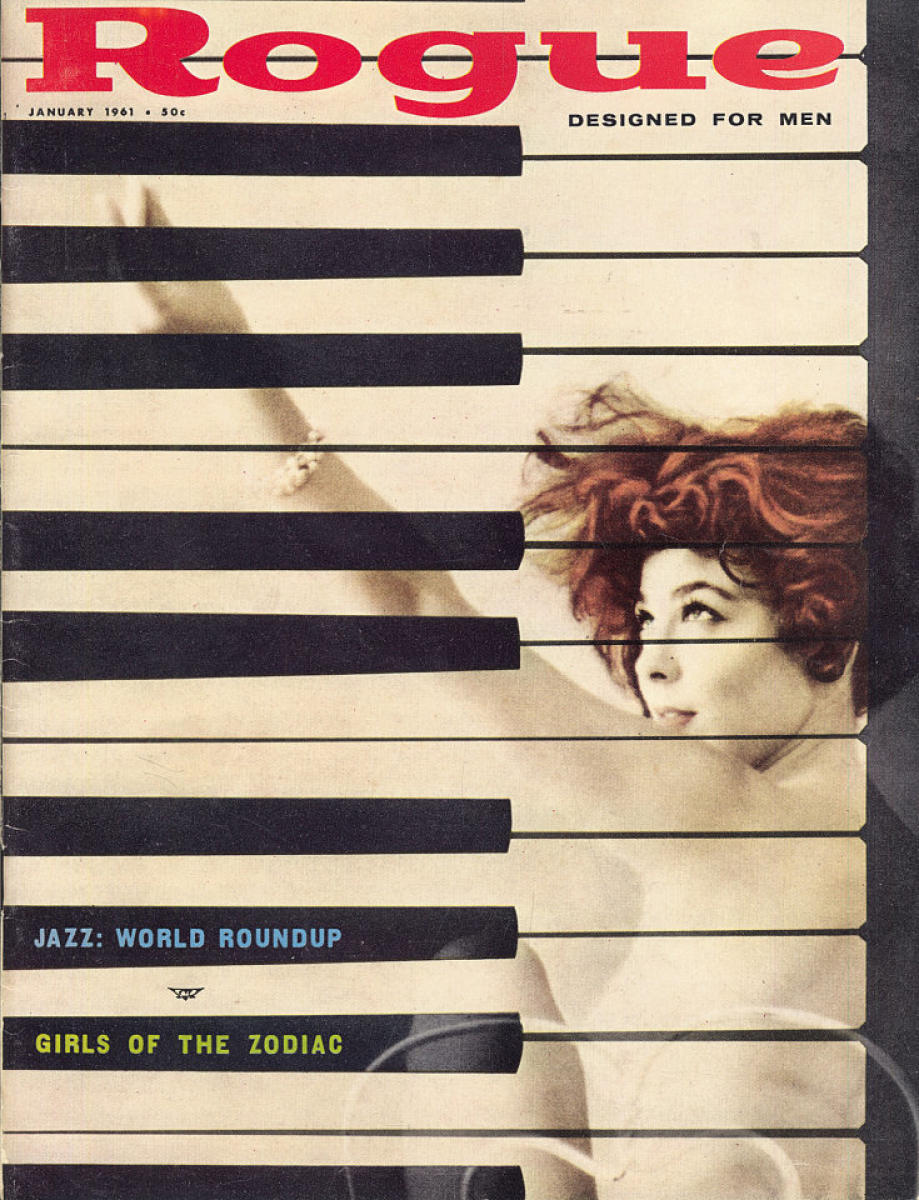

The piece that White wrote, “Riot at Newport,” was based on info gleaned from news reports and from his friends who were there, such as Bob Perlongo. It was published in the January, 1961 issue of Rogue with Tina Louise on the cover. Ted White gave much credit to the editor Frank Robinson for the quality of the final story, but even so, his first sale to Rogue was about a major event in the jazz scene and he was certainly off to a good start!

Who were the other young writers being published by Rogue? One of them was Hunter S. Thompson, whose first paid publication was “Big Sur: The Tropic of Henry Miller” (Oct, 1961). In Thomspon’s piece you could feel the editorial slant of Rogue. They projected an image of liberal, risqué commentary, without being too serious, coming from their staff of literary correspondents around the globe.

But the roving reporter at Rogue wasn’t Hunter Thompson. It was Dave Stevens, who wrote the “Rogue about Town” column. Stevens was soon poached by Playboy, where he wrote a similar column for more than 30 years.

Clearly Rogue was more than just a girly magazine with photos of nude women. They published everything from gag cartoons, to science fiction, to humor. The magazine was as flip as you could get, pushing the edge of tastelessness towards the judgement line of obscenity, which they eventually crossed.

To his credit, Hamling paid for the legal fees of his employees when they were eventually busted for obscenity. Some of the cases made it all the way to the Supreme Court.

The obscenity case directly related to Rogue was about distribution through the US Post Office. The case was decided in Rogue‘s favor in 1957, which paved the way for both Rogue and Playboy to be legally mailed to any address in the USA.

While Playboy could pay top dollar for the best artists and writers in the country, Rogue took risks on young, unkown writers with talent. Rogue might publish a piece by the best known jazz writer of the day, Nat Henthoff, but they also bought pieces by aspiring young writers like Ted White. As the scrappy challenger to the leading magazine in a new genre, Rogue was the underdog.

Take the case of comedian Lenny Bruce, whose risqué jokes and routines were famous in the strip clubs of the San Fernando Valley but too obscene for popular publication. Hugh Hefner was a big fan and used his influence with nightclubs in Chicago to have Bruce perform in the city’s top venues. Although Hefner and Playboy supported him from the start, it was Rogue that published Lenny Bruce first: “The Money I’m Stealing,” in November, 1959.

Playboy didn’t actually publish his writing until 1964, so it’s an important to note that Lenny Bruce was holding up a copy of Rogue Magazine, not Playboy, at the Chicago nightclub in 1962 when the police raided the joint. He was arrested in mid-performance, right on the stage.

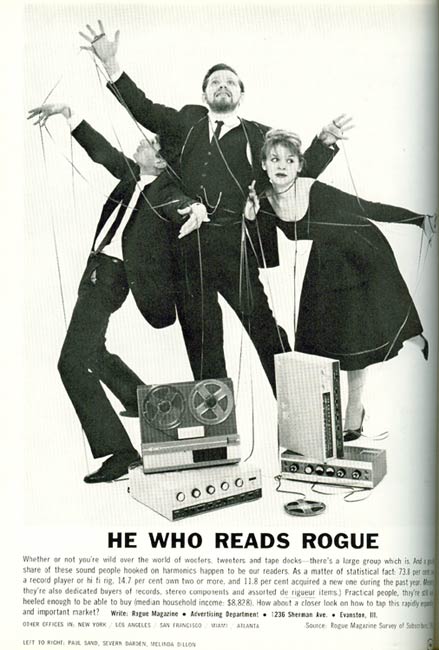

With a wild sense of humor and willingness to take risks, Hamling and the editors of Rogue created a dynamic energy that rivaled Playboy. Lacking pots of money to throw around, Rogue was more of the upstart. Like Jay Ward Productions in Los Angeles (creators of Bullwinkle), Rogue substituted zany publicity for cash.

In one publicity campaign, called “He Who Reads Rogue,” the Second City actor, Severin Darden, posed with two people from the Rogue office. They waved their arms in dramatic poses while tangled in reel-to-reel audio tape. This advertisement was typical of the absurdist view that Rogue had of itself and everyone else.

Rogue Magazine, breaking away from the conservative expectations of the 1950s hit a high note in 1961. That year, editor Frank Robinson recruited Ted White to report on the “beatnik riot” that took place in Greenwich Village in April.

Once again, Ted White was writing about an event that he hadn’t seen with his own eyes. But in the story he produced, “Balladeers and Billy Clubs,” he felt that he was beginning to feel confidence in his own chops as a writer.

Since he lived on Christopher Street, and was writing about the jazz clubs in Greenwich Village, Ted White already had a good feel for the story. He immediately went to find Izzy Young, whom he knew as the owner of the folk music store on Macdougal Street. As it turned out, Young played a pivotal role in the affair and Ted White was able to tell the story from the center of the action.

When Izzy Young read the draft of the article, he was amazed by how accurately White had captured their conversation from only a few scribbled notes. White said that he learned an important lesson from that. People being interviewed won’t have an exact recollection of every word that they said, but if you get the mood right, they will feel as though it was a word for word transcription.

With those two articles, Ted White began his career as a writer in slick magazines. He was writing about music and society on the eve of the civil rights movement, about people who were standing up for the right to sing in the park, and people who chose to integrate themselves however they wanted to as a measure of their own freedom.

American kids everywhere were driving around in search of their own kicks, creating their own scenes that sometimes turned wild and violent. While America was on the road in search of itself, Ted White captured a moment of history by going Rogue.

References:

Baker, Joe, “LOOKING BACK: 1960 Newport Jazz Festival riot,” in Newport Daily News, (12 Dec 2012) src

Bruce, Lenny, “The Bust Show, Gate of Horn, Chicago,” audio archive of Brandeis University (5 Dec 1962). src

Drasin, Dan, Sunday, a film by Dan Drasin (9 Apr 1961). src

Gallagher, Paul, “New York City’s Beatnik Riot, How Singing the Star Spangled Banner Kicked Off the 60s Revolution” in Dangerous Minds (7 Mar 2016). src

Jackson, Ashwanta, “The Newport Rebels and Jazz as Protest” in JSTOR Daily (23 Jul 2020). src

Kemp, Erle, eI 11, Vol. 2 No. 6 (Dec 2003). src

Myers, Marc, “George Wein on the Rebel Festival,”” in JazzWax, (2 Jul 2010) src

Robinson, Frank, Not So Good, A Gay Man (2017). src

Strausbaugh, John, “3000 Beatniks Riot,” in The Chiseler (2013). src

Thompson, Hunter, “Big Sur, The Tropic of Henry Miller,” in Rogue (Oct 1961). scan

Tucker, Bob, “Chicago Express,” in SaFari No 2 (Jul 1959). src

White, Ted, “Interview with John D. Berry,” hosted by Fan History Project, (23 Jan 2021). src

White, Ted, “Balladeers and Billyclubs” in Rogue Magazine v6 no8 (Aug 1961). src

White, Ted, A Ted White Sampler, Vol 1 edited by Arne Katz. (Originally in Mimosa #12, 1992). src

White, Ted, “Riot at Newport” in Rogue Magazine v6 no1 (Jan 1961). src

White, Ted, “Two Editors: Frank Robinson and Bruce Elliott” in Earl Kemp’s eI v2 no6 (Dec 2003). src

Wilson, John K., “Sci-Fi Legend’s Life in Evanston,” in Evanston Roundtable (25 Jul 2018). src