It’s a good thing that Michael Gonzalez reposts his terrific essays on modern Black authors every now and then. These originally appeared in a column called the BLACKLIST for Catapult Magazine. Every time I read one of these essays, I spend a worthwhile amount of time digging back through journals, movies, novels, and book reviews to discover more and more about the these incredible authors and the world they lived in. Kudos to Michael!

The review of Julian Mayfield’s novel The Long Night was no exception to this pattern. When I read about Mayfield being published in a 1960 Cuban magazine called Lunes de Revolución, I had to know more.

According to William Luis, this publication was the literary supplement to the official newspaper of the Cuban revolution, the 26th of July Movement’s Revolución and was distributed on Mondays, thus the title “Mondays with Revolution.” Mayfield’s article appeared in a special issue called “Los Negros en U.S.A.” which featured a number of other writers such as LeRoi Jones, Langston Hughes, Alice Childress, and James Baldwin.

Fortunately, the entire “Negroes en U.S.A.” issue of Lunes de Revolución [Mondays with Revolution] is scanned and available online. In all, there were 13 authors who appeared in that 1960 anthology, published in Havana, Cuba. Many of the articles included were appearing for the first time in Spanish, having yet to appear in their original English versions.

Let’s take this opportunity to flesh out some context for each and every one of these authors. To be sure, they all had some backbone to publish anti-colonial essays in Cuba during the first year after Castro had overthrown the Batista regime. And yet, those were different times!

Castro’s visit to NYC in 1959 and again in 1960 were amazingly open and festive. The mood among the Left activists was upbeat and energized, which definitely contributed to the FBI and CIA taking a keen interest in their activities.

Some of the authors in Lunes de Revolución were already famous, lending their imprimatur to the volume, while others were newcomers.

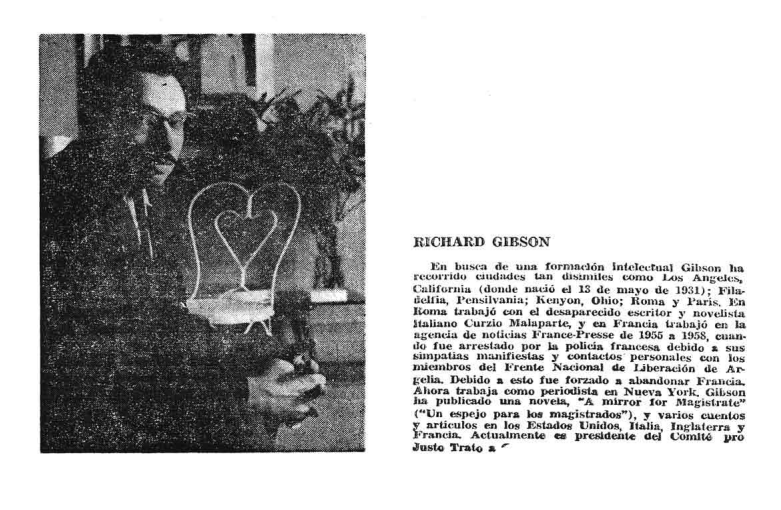

Richard T. Gibson

The first piece in the magazine is Richard T. Gibson’s El Negro Americano mira hacia Cuba [The Black American Looks towards Cuba] where Gibson reflected on liberation movements and their origin in Africa and Asia. Gibson had lived in Paris in the 1950s and according to the small biographical note in Lunes de Revolución was forced to leave France over his close association with the National Liberation Front. In the 1960s, Gibson was a co-founder and president of the Comité pro Just Trato a Cuba [Fair Play for Cuba], and was purported to be the original model for the spy character in Richard Wright’s final novel Island of Hallucination.

James Campbell examined the mystery of Wright’s unpublished novel for the Guardian, and had this to say about Gibson’s time in Paris:

“a photocopy of Island of Hallucination, more than 500 pages in Wright’s typescript, came into my hands, by an unexpected route: it was lent to me by Richard Gibson, whose presence in the novel is thought to have been behind its suppression. Now in his 70s, Gibson, who was born in Los Angeles and raised in Philadelphia, has lived in west London for many years. He talks readily about a colourful past that involves various political affiliations and adventures, disgraces and protestations of innocence. In the early 1960s, he was head of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in the United States, in which capacity he met Fidel Castro and Ché Guevara on several occasions.

When John F Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Gibson was approached by the CIA for information on Lee Harvey Oswald, who also had links with the FPCC. He is the author of the book African Liberation Movements, and was for a time English-language editor of the Algiers-based magazine Révolution Africaine , run by the French lawyer Jacques Vergès, who later denounced Gibson in the magazine (July-August 1964).

Since his Paris days, when he was a regular at the Café Tournon, Gibson has had to fend off suggestions of egregious activity, including spying for the US government, allegations he has consistently denied, sometimes in the law courts and sometimes with a touch of humour. “If I’m CIA, where’s my pension?”, he once quipped to me.

Gibson is painted in a harsher light by Charisse Burden-Stelly where his various denials and prevarications are upended. The author cites examples in Gibson’s letters in which he declared that all those who questioned his affiliations were themselves tools of the CIA, imperialism, Trotskyism, or revisionism. So was Gibson a spy?

Yes. According to Newsweek, among the JFK related files unsealed in April 2018 were “three fat CIA files on Gibson. According to these documents, he had served U.S. intelligence from 1965 until at least 1977. This was well after Wright wrote his book, and it’s not clear if Gibson had engaged in espionage before that period.”

Isn’t it tragic for us, in hindsight nearly sixty years later, to be piecing together the threads of all these operations; trying to figure out the patterns of complicity, betrayal, and ideological motivations that existed at the very heart of our struggles for freedom? When the keenest of minds were either driven crazy by suspicion, or were selling out to various intelligence services, does that change the meaning of the tribunals and declarations they proclaimed? Does that dilute the act of revolution, knowing that the CIA, KGB, or other forces were constantly playing a hidden hand?

Then again, we shouldn’t romanticize the engagements between revolutionary and counter-revolutionary forces that took place in the 1960s. This shit’s been going down since the dawn of time. Instead we should take advantage of one real difference that the 60s gave us: profuse documentation.

Taking the cue from I. F. Stone (who read between the lines of Korean War reporting) perhaps we can unravel the public statements of people like Richard T. Gibson, in light of the CIA documents that come to light.

Were Gibson’s writings about U.S. imperialism and resistance empty of substance? As the editor of Revolution Africaine when the publication offices moved from Switzerland to Algiers, it’s absurd to think that he was not well informed. He was unquestionably a central figure in the community of Black thinkers and writers who promoted an anti-colonial and revolutionary synergy with struggles taking place in Latin America, Africa and Asia, the “tricontinent” sphere of resistance to the UN and US model of world order. So the question is one of when Gibson’s involvement with CIA began and whether that changed his tune.

Gibson had covered the Cuban revolution for CBS News in the late 1950s. In 1960 he was a founding member of the Fair Play for Cuba organization, which clearly explains why his contributions are the openers for Lunes de Revolución from the same year.

He must have been on the radar of the CIA in 1961 when he was called to testify about his communist affiliations before the US Senate Internal security

Sub-committee. At that time, Gibson refused to answer all questions and allegations about communist affiliations.

The critical year must have been 1962 to 1963 when Gibson quit the Fair Play for Cuba Committee and became the English editor for Revolution Africaine. Certainly by 1964, he was already being denounced as unreliable in the very pages of that journal by it’s publisher, Jacques Verges. So it makes sense that the CIA documents show his employment to have been official by 1965.

Another real mystery is to figure out if Richard Wright’s character accusation in Island of Hallucination was already true at time it was written – before 1960. Was Gibson feeding information about his colleagues in Paris back to Washington? Or did Wright’s accusation serve as a galvanizing factor in Gibson’s decision to work as a spy? Perhaps somewhere in the tenor of his own writings or in the redacted goverment documents we will find the answer.

References:

Burden-Stelly, Charisse, (2018) ‘Stoolpigeons’ and the Treacherous Terrain of Freedom Fighting in Black Perspectives

Baldwin, James, (1949) “Everybody’s Protest Novel”, Zero (Spring 1949).

Campbell, James, (2006) “The Island Affair” in The Guardian

Fabre, Michel. 1993. The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright. 2nd ed. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Gibson, Richard T., Papers.

Gibson, Richard T., (1965) “A Maoist in France: Jacques Vergès and Révolution” in The China Quarterly No. 21

Luis, William, (2002) “Exhuming Lunes de Revolucion” in The New Centennial Review Michigan State University Press

Volume 2, Number 2, Summer 2002

Michael Gonzalez: “The Long Night”: A Novel by Julian Mayfield (2018) in Catapult

Lee, Christopher J. and Anne Garland Mahler (2020) The Bandung Era, Non-alignment

and the Third-Way Literary Imagination in The Palgrave Handbook of Cold War Literature

Lunes de Revolución “Los Negroes de U.S.A.” (4 July 1960) The Internet Archive

Lunes de Revolución (11 May 1959) Univ of Florida Digital Collections

Morley, Jefferson (2018-05-15) CIA Reveals Name of Former Spy in JFK Files—And He’s Still Alive in Newsweek

Saba, Paul and Sam Richards, (2020) “Notes on Révolution, Gibson and Vergès” in Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line